Why are seniors disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 and other communicable diseases?

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a rapidly spreading infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). We still have a lot to learn about the deadly SARS-CoV-2; however, what we know with certainty is that it disproportionately affects adults with advanced age and underlying comorbidities. As of June 2020, the CDC reports that adults age 65 and over account for 80 percent of all COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. Sadly, this virus has been particularly fatal for residents of both nursing homes and group living facilities. Of the 103,000 COVID-19-associated fatalities in the U.S. as of June 2020, an alarming 42 percent have been in these facilities. A cursory look at previous communicable diseases reveals that seniors have always been the most vulnerable to infections such as influenza, flu and others. In this article, we examine the pre-existing conditions that put our aged adults at high-risk from COVID-19 and other illnesses.

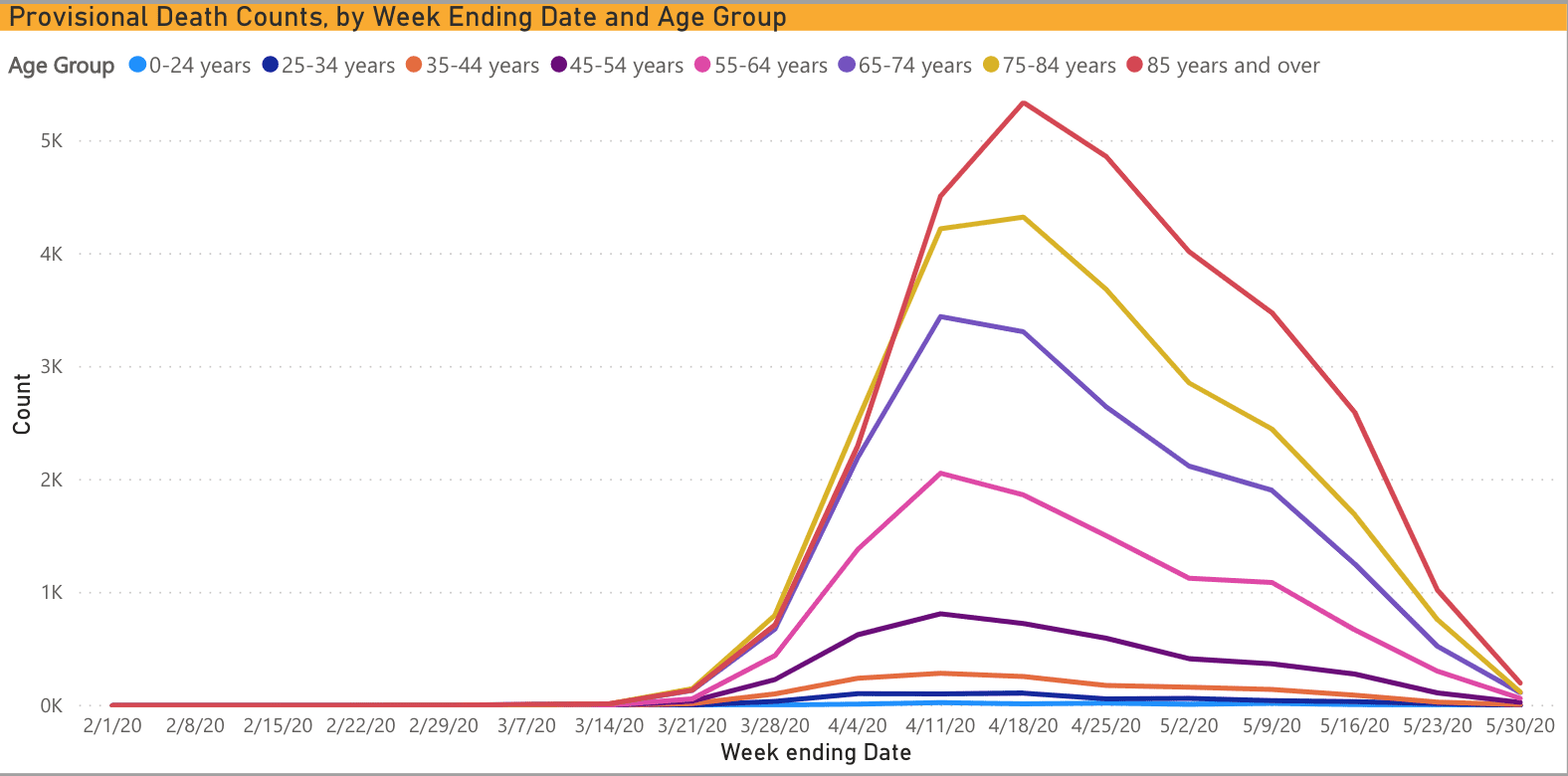

Figure 1. COVID-19 deaths by week and age group in the U.S. (CDC data as of May 30, 2020)

How aging and underlying conditions contribute to hospitalizations and death from COVID-19?

The high case fatality rate and the severity of the COVID-19 disease to seniors, has left scientists scrambling to figure out the underlying conditions for older people’s greater susceptibility to the virus. While research is ongoing, scientists have pegged the vulnerability to three crucial factors: (i) the overall decline of the immune system as we age; (ii) hyper-activation of the immune system resulting in cytokine storms; (iii) pre-existing chronic conditions.

Immunosenescence:

The number of virus particles a person is exposed to — known as the “infectious dose” — determines the likelihood and severity of an infection. The minimum infectious dose for COVID-19 is unknown, but studies suggest it is low. Viruses with low infectious doses are known to be especially contagious in populations with a dysfunctional immune system. Seniors are immunocompromised due to a phenomenon known as immunosenescence, defined as the gradual decline in the immune function as we age. The impaired functionality of a senior’s immune system hampers pathogen recognition making it possible for a low dosage of virus to easily survive and replicate rapidly.

Cytokine Storm:

When the immune system eventually responds, there is a high likelihood of it going into overdrive, especially in older adults. This process is known as a ‘cytokine storm.’ Cytokines are small proteins that serve as the body’s response against infection and trigger inflammation. When excessive or uncontrolled levels of cytokines are released, it causes hyper-inflammation, high fever and eventually organ failure. According to a recent study, one in two fatal cases of COVID-19 experienced a cytokine storm and 82 percent of the cases were over the age of 60. Cytokine storms are a common complication not only of COVID-19 and flu, but of other respiratory diseases caused by coronaviruses, such as SARS and MERS.

With seniors, there is also a gender bias when it comes to a surge in cytokine production in the body. A recent study showed that on average older men had more cytokine-producing cells than older women. This finding may help explain the gender-based differences in the COVID-19 epidemic, with older men faring worse than older women.

Comorbidities

Apart from declining immunity, pre-existing chronic conditions can also aggravate the effects of COVID-19 in seniors. Comorbidity is the presence of two or more clinical conditions in a person. Approximately 80 percent of older adults in the U.S. have at least one chronic disease, and 77 percent have at least two. A survey of members of a health maintenance organization ages 65 and over found the average person had 8.7 chronic diseases. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association characterized the symptoms, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes of 5,700 patients hospitalized in New York from COVID-19. The study found that 94 percent of the patients had a chronic health problem, and 88 percent had two or more. The three most prent conditions were hypertension (56.6 percent), obesity (41.7 percent), and diabetes (33.8 percent). In a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak across several long-term care facilities in Washington State, the median age of the facility residents affected was 83 years, and 94 percent had a chronic underlying condition.

How does COVID-19 affect seniors?

It is not just that the disease affects seniors severely, it also happens to affect them in different ways than it does people below the age of 65 years.

Atypical symptoms

According to the WHO-China joint commission report, the signature symptoms of COVID-19 include — fever (88 percent), dry cough (68 percent), fatigue (38 percent), sputum production (33 percent), and shortness of breath (19 percent.) However, people over 65 years of age, the population most at risk of severe illness from the infection, may not show any of these typical signs. Instead, seniors show changes in their daily activity and behavior patterns – such as sleeping more than usual, not eating, or appearing disoriented and confused. They may also have more instances of falls. These atypical characteristics can once again be attributed to age-related responses to infection. A dysfunctional immune system may affect the ability to regulate temperature and underlying chronic conditions may alter the cough reflex. A geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center in Switzerland has compiled a list of typical and atypical symptoms seen in older COVID-19 patients in a forthcoming paper. The symptoms include changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of smell and taste.

Asymptomatic Seniors

Apart from showing atypical symptoms, there have been a significant number of seniors who are asymptomatic. The CDC performed symptom assessments and SARS-CoV-2 testing for residents of a skilled nursing facility in King County, Washington showed 23 (30 percent) residents with positive test results, 10 (43 percent) had symptoms, and 13 (57 percent) were asymptomatic on the date of testing. Seven days after testing, 10 of the 13 asymptomatic residents had developed symptoms and recategorized as presymptomatic at the time of testing. This finding is significant because it suggests:

- Symptom-based screening of residents may fail to identify individuals (residents, visitors and staff) infected with SARS-CoV-2 but are not yet symptomatic.

- Transmission from asymptomatic or presymptomatic individuals, who were not recognized as a probable COVID-19 carrier and were therefore not isolated, might contribute to further spread in a community.

Nursing Homes and Senior Living Facilities at a disadvantage when it comes to communicable diseases

It is not just the fact that senior living facilities and nursing homes house a population already vulnerable to infections but also the nature of the service they provide that makes them the ideal breeding grounds for coronavirus. Here are some of the factors that contribute to an outbreak:

(i) These high-risk settings house a population that is extremely vulnerable to severe illness from COVID 19. Once an infection enters the facility, it can quickly spread due to the compromised immune system and pre-existing conditions that are prent in seniors.

(ii) Residents live in close quarters in these communities, often sharing rooms posing challenges for proper social isolation and quarantine.

(iii) According to the CDC, at least half of the older adults living in these care facilities have Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia, which adds a new layer of complexity to control the infection – one such specific challenge is that people with dementia and other cognitive impairment may not fully comprehend the dangers of infection. Hence, enforcing safety precautions such as washing hands or practicing physical distancing may be difficult.

(iv) Seniors living in these facilities need a lot of basic care that requires frequent close physical contact between staff and residents. Close contact is critical even in assisted facilities that do not provide the same level of medical care.

(v) Staff members care for multiple residents, thereby becoming a primary disease vector.

(vi) Staff members sometimes work at various facilities, increasing the risk of contracting the disease and bringing it into the facility. All these factors contribute to making nursing homes and senior living facilities a hot zone for the highly transmissible virus.

Contact Tracing is one of the effective infection control measures available to facilities to stop the spread of infectious diseases. However, given the high-density and high-risk attributes of these facilities, effective contact tracing needs to be rapid, automated, and encompass multiple layers of tracing of people and places exposed to the infectious virus.

Related Blogs